“I’ve never heard anything about this event before. Ever!” said my big sister after reading my son Zeke’s book report back in May 2021. “What a fascinating paper!” That’s a pretty ringing endorsement considering that my oldest sis is both extremely well-read and quite the history buff.

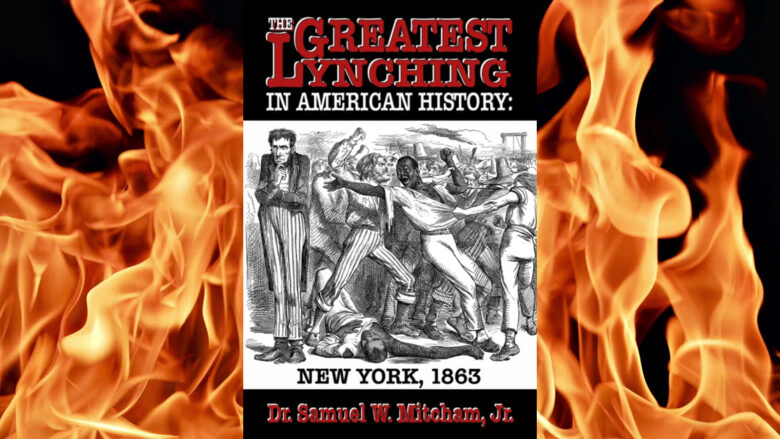

So, just what was the book my then 12-year-old son had written about? Answer: “The Greatest Lynching in American History: New York 1863” by Dr. Samuel W. Mitcham, Jr., made available by the fine folks at Shotwell Publishing.

But a lynching … in New York? And in 1863 no less? But wasn’t this when Lincoln’s “grand army of the republic” was fighting to free the slaves?

Wasn’t it only the knuckle-dragging dolts down in Dixie who lynched black folks who were, of course, the only people ever lynched? Right? I mean, Billie Holiday told me so in “Strange Fruit” when she crooned the famous song written by avowed communist and native New Yorker Abel Meeropol.

I had forgotten all about Zeke’s homeschool paper, that is, until I recently interviewed the provocative writer and independent historian Valerie Protopapas. In the first few minutes of our conversation, Protopapas, who herself is a New Yorker (but is all Copperhead and in no way Yankee), mentions the NY draft riots which spawned “the greatest lynching” and this jogged my memory.

So, I’ve decided to cross-publish Zeke’s essay. I’m not trying to score any “thems the real racists” points or participate in surrogate atonement for the “white guilt” elites say I should have. Honestly, I have no interest in working within the putrid progressive paradigm of racialist obsession, especially one that has white folk always playing on the defensive.

Rather, this is about taking the offensive via myth-busting. Think about it: if Yankees weren’t the holy warriors for the cause of immediate emancipation and aren’t the ultimate “saviors” to the black man, the entire presentist narrative of the War (and the revolutionary spirit born of it) must be called into question. I simply want people to stop and think.

“Mom, did you know that …?” Zeke would excitedly say while devouring the book. “Guess what I just read!” He was astounded with the topic as well as the author’s storytelling style (which we were already familiar with having listened to Mitcham’s “Bust Hell Wide Open: The Life of Nathan Bedford Forrest” on audiobook), so I instructed Zeke to write a narrative synopsis with all the newfound knowledge he’d gleaned. He’s a date-and-numbers kinda guy, so I figured he’d have fun with this approach.

Don’t worry, though. Zeke doesn’t give it all away. There are many more shocking details within the book’s pages. Hopefully, you will like my son’s treatment (both his words and the photos he chose to help illustrate his essay) as much as my big sis, and that it whets your appetite for digging deeper into this hushed event. Perhaps it will even inspire you to question even more “consensus” historical narratives, putting a much-needed chink in the armor of the Yankees’ pretend purity.

“The Infamous but Unknown Insurrection: The New York City Draft Riots of 1863”

By Zeke Dillingham

May 2021

The New York City Draft Riots took place from July 13 – July 17, 1863 in New York City, New York. Irish Immigrants and other white New Yorkers felt like they had been somehow scammed by their government, and now they were forced to fight a war to supposedly “free the slaves,” while competing with freed blacks in New York for low-wage jobs. These riots were more like a revolt or insurrection than a protest, and police, army, and navy were sent in to fire on the mob. Even though they’re unknown by most people, these were the worst riots in American history [Editor’s note: until the 2020 BLM riots] and the bloodshed was quelled only after four harsh days of fighting in the streets.

Colonial New York City

New York City was founded as the Dutch colony New Amsterdam in 1609, and after sparring over the city for decades, it was finally ceded to the British in 1674. It had a surprisingly large slave trade industry, and in 1703, 42% of all households owned slaves. In 1712, there was a slave revolt which resulted in the death of nine whites. Seventy suspects were arrested, and then were burned to death and placed on the breaking wheel (a form of torture where the victim’s limbs were broken and then he was strung on a wheel and left to die). There was another slave revolt in 1741, and more than 350 suspects were hung, scorched to death, or gibbetied (a torture method where the victim is left in a public to starve or die of thrist).

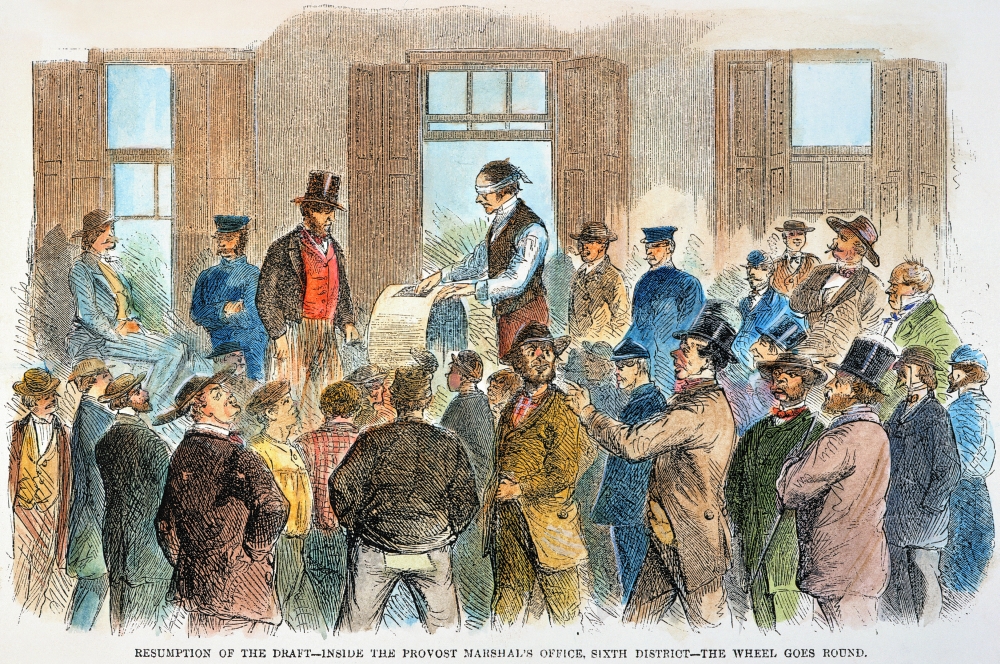

Leading up to the riots

New York outlawed slavery in 1830, however, in the 1850s and early 60s, the city’s poor population and Irish immigriants were angry at Republicans and the rich of the city, but especially at the blacks for “stealing” their employment oppurtinunities. When War Between the States broke out in 1861, New York City was at first ready to fight the “traitors” in the South, but when Lincoln’s War wasn’t over quickly, the citizens of New York became anti-war. After the Emancipation Proclamation was delivered on September 22, 1862, trying to change the meaning of conflict from preserving the Union to supposedly freeing the slaves, and the enrollment act (the draft) was also passed on March 22, 1863, the people of New York were enraged with their government which was forcing them to fight for the men they hated: The Republican politicians, the wealthy, and the freed blacks.

The first day (July 13, 1863)

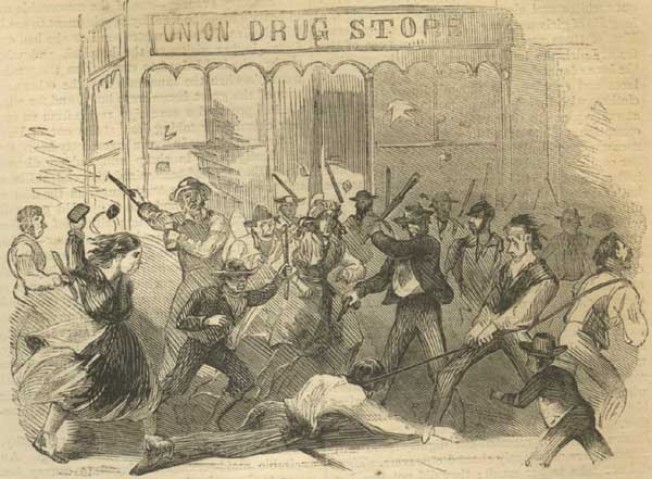

On the morning of July 13, 1863, rioters sacked a draft station on 3rd avenue. At 9:30 a.m., Police Superintendent Kennedy left headquarters to inspect the situation by himself, and went where the mobs were on foot. They recognized him and tried to kill him, but six of his men were nearby and saw that he was in danger, so they tried to help him but were overwhelmed by the bloodthirsty crowd. The mob then proceeded to drag him into an alley, beat him almost to death, and stab him several times, and tried to drown him in a mud puddle. The Superintendent barely got away and was rushed to the station.

The mob grows

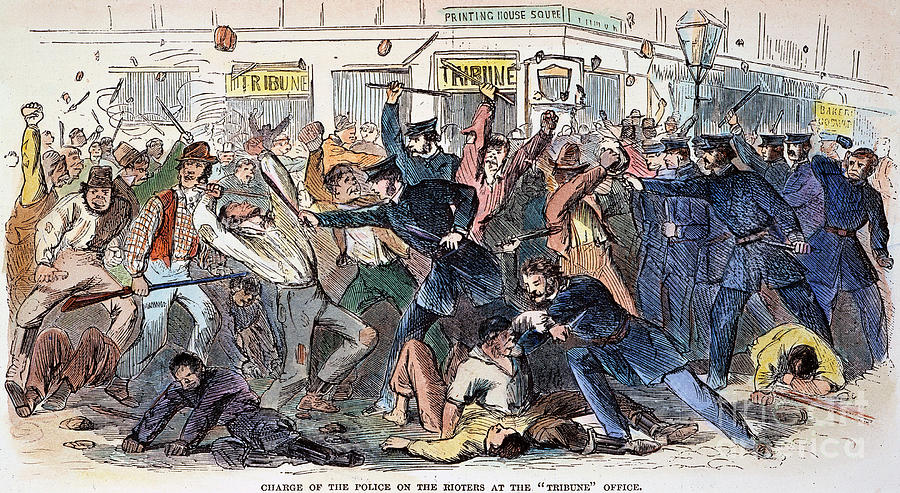

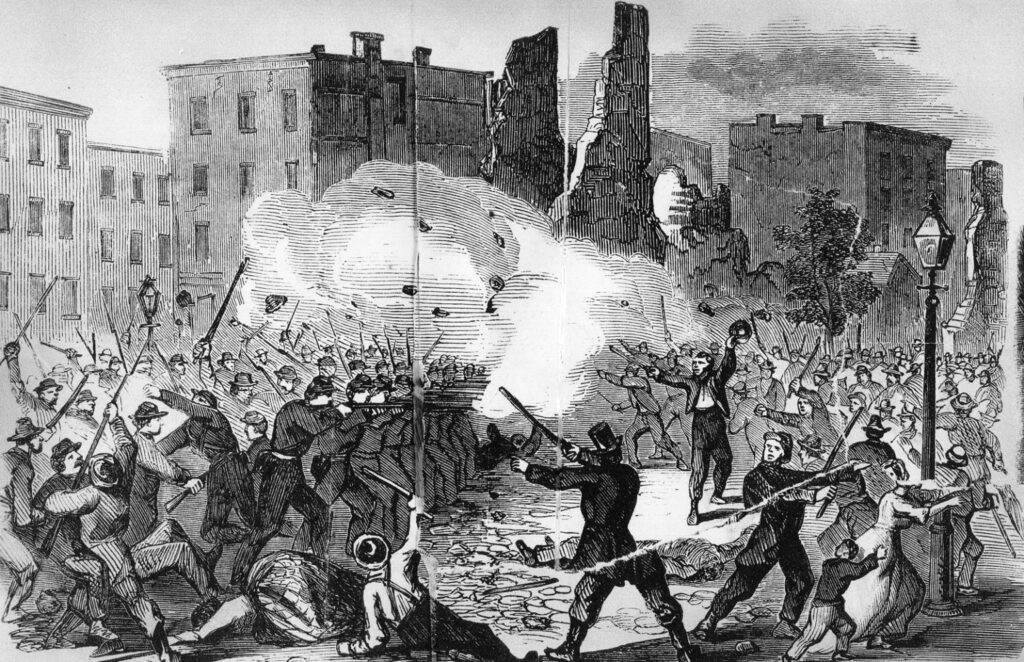

Later in the day, rioters cut down telegraph wires. Around 10:00 a.m., 50 police men approached the enrollment office but were too late. The rabble were on top of buildings and hurled rocks and stones down on the police, and in retaliation, the police sent a volley of fire at the irate Yankees, killing and wounding several. Still, the police ran away, and some survivors were caught by the hoard and thrown off a bridge. When the mob got to 46th street, they were quickly surrounded by Sergeant Robert A. McCredie and 14 officers, who tried to attack them with their clubs, but the rioters sent the bluecoats running and only 5 out of 14 of the police were not injured. Cruelly, wounded police who were left in the streets were stoned to death. It was now the afternoon of July 13, and there had been 20 skirmishes so far in which the police had lost every time. Moreover, evey well-dressed person was either beaten or killed by the mob.

The battle at the armory and the banks

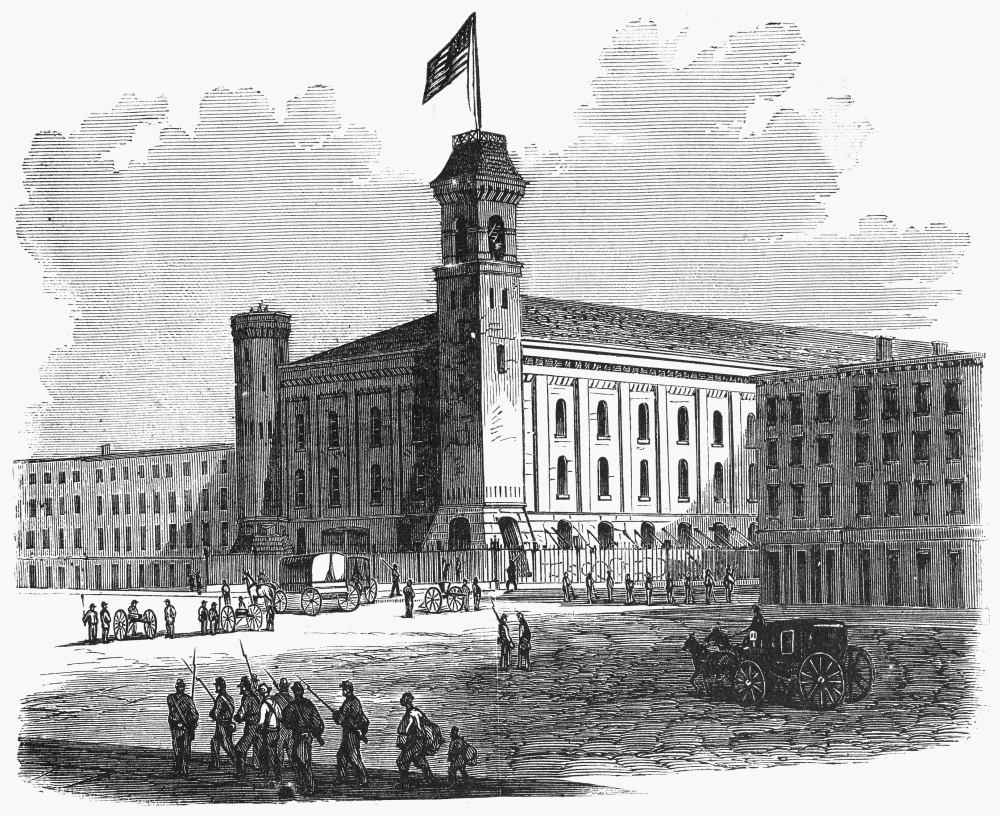

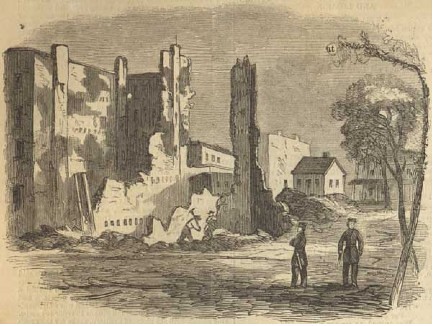

Four-hundred men of the New York National Guard were sent to the armory to protect the guns and ammo there, where they were met by a mob of 5,000 who threw rocks and shot through the windows at the army and police inside. The rioters tried to get in the front entrance, but the army sent a volley of fire with their rifles, killing several and wounding a good amount. Eventually, the army and police saw that there was no hope of defending the armory and escaped through the back entrance, which allowed the mob to steal the guns and ammo and burn the place to the ground. Meanwhile, a massive mob advanced towards Wall Street to burn down the banks but was stopped by a hefty force of police who were armed only with clubs. Many rioters and police were killed and a lot more were wounded. This fight finally ended at 5 p.m.

The orphanage

Simultaneously, a mob of 3,000 people attacked the Colored Children’s Orphan Asylum [images above] on 43rd and 44th streets. It housed 500 children, but 233 were there on July 13, and all were under 12 years old. The superintendent of the orphanage saw the rioters coming so he locked the front door, and he and the children escaped through the back exit which allowed the mob to break in. Luckily, none of the children were hurt, but the building was burned. When the fire department arrived, they tried to put out the fire, but the Chief Engineer was beaten by the ferocious gang. Throughout the evening and night of July 13, the throng continued attacking African-American and rich residents of the city.

The second day (July 14, 1863)

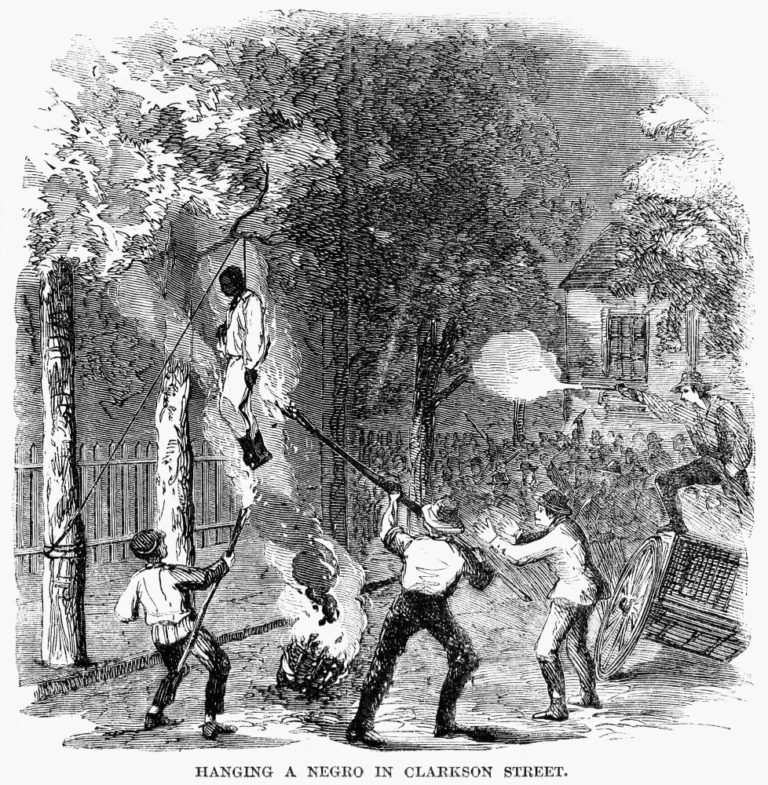

On the morning of July 14, hotels and other buildings were burned by the mob, while naval and army reinforcements were called to the chaotic city. Veterans of previous wars were recalled to the army for more help. The streets were dangerous the second day, lynched people both black and white could be seen on every lamppost, and half of the city was on fire. At 10:00 a.m., the cabal and the army had a chaotic battle at 34th and 35th streets, and many lives were lost and people maimed. Later, the 11th New York army regiment commanded by Colonel Henry O’Brien shot at the mob with artillery, which resulted in the death of many rioters. For the rest of the morning, the fires and the killing of blacks and the rich persisted. The city was strewn with debris, flames and smoke, and the bodies of dead and dying people.

Deadly afternoon

By this point, most of the rioters had guns and were engaged by the police at 2nd Avenue. Even though the police had mostly clubs, they still sent the unhinged crowds running with only a few police casualties and none killed. They wounded and killed many rioters, and even took out mob leader Henry Hedden. There was more bloodshed later in the day, with one engagement leaving 21 rioters dead alone. The afternoon of the second day was the harshest fighting of the riots, and the mob again focused on black civilians. They were lynched by the dozens, and not even the elderly and young children were spared. At the harbor, black sailors were hung and their bodies burned, and some were also stoned and beaten to death.

The death of Colonel O’Brien and the Derricksons

An exhausted Colonel O’Brien was walking alone to his house, when he was captured by rioters who tortured him almost to death and dragged him outside by his hair and left him for dead on the street. A friendly man attempted to give the Colonel water, but the mob sacked and burned the man’s house, engulfing it in flames. After the rioters were gone, other neighbors tried to help O’Brien. They rushed him to the hospital, but he was already dead. Those who aided were brutalized and their houses were set ablaze. Later that night, the Derrickson family were attacked in their house by a band of rioters. Mrs. Derrickson, who was white, was beaten and stabbed half to death with an axe. Luckily, she was saved by a squad of helpful German immigrants, but her young mixed-race son was lynched and his body burned.

The third day (July 15, 1863)

By the early morning of July 15, the rioters continued to destroy African-American homes and churches. At 9 a.m., they started lynching blacks on 32nd street as Colonel Thaddeaus Mott arrived with his men. The mob tried to pull him off his horse, but the army fired cannons into the crowd, killing dozens and wounding many more. There was more fierce fighting throughout the morning. For example, at one battle 40 rioters were killed and many more were wounded with soldiers also suffering bad casualties. There was more violence into the afternoon. Colonel Jardine was mortally wounded by a rioter’s gun later that evening.

Other wounded soldiers who lay dying on the street were finished off. There was more sharp fighting, and the mob shot at the police and army in volleys.

The fourth day (July 16, 1863)

On the morning of July 16, there were not as many rioters in the streets as before, and more and more troops were pouring into the city. There were a few skirmishes that were mostly won by the police and army. By the afternoon, most of the suspects were rounded up, and by evening all violent activity in the streets was gone.

Aftermath

Overall, the riots claimed many lives of civilians, rioters, police, and army. The official government number of deaths is 120 killed and 2,000 wounded, but many of the fatalities were not reported and the dead simply buried along the roadsides. Many other sources estimated much higher death tolls. However, most original media reports were between 1,000 and 2,000 deaths and almost 8,000 wounded, making it the deadliest riot in American history. The revolt caused about 1 billion dollars in property damage in today’s money. This infamous insurrection is unknown by most people but is vital to understanding the Civil War and its aftermath.

Be sure to visit Shotwell Publishing to pick up your copy of “The Greatest Lynching in American History: New York 1863” by Dr. Samuel W. Mitcham, Jr., or one (or a few) of their other unreconstructed works. Any of Shotwell’s books will make a great Christmas gift for Dixians, Copperheads, and Yankees alike.

Comments

You are so silly to add your nonsensical editor’s note: these were the worst riots in American history [Editor’s note: until the 2020 BLM riots] . Yet you say you have no interest in working within the putrid progressive paradigm of racialist obsession, especially one that has white folk always playing on the defensive. Sounds pretty defensive to me.

Keep your funny papers going.

Author

So, offering up a correction with a link which explains the size, scope, and price tag (not to mention institutional approval) of the 2020 riots isn’t a defensive thing; it’s called stating fact. Moreover, it seems that you, dear Robert, are tacitly admitting that the BLM/Antifa/deep-state riots were about anti-whiteness and POC supremacy. Another unequivocal fact. Sheesh, thanks! And thanks too for reading my funny paper. Your triggered response gives me hope that perhaps you learned a thing or two. 😘

was there a last international slave ship departing the northeast about this time as well…web dubois claiming so.

“Overall, the riots claimed many lives of civilians, rioters, police, and army. The official government number of deaths is 120 killed and 2,000 wounded, but many of the fatalities were not reported and the dead simply buried along the roadsides. …” were these all the wonderful arrivals from the ‘revolutions of 48 across europe’? desiring an end to a crown there but destruction of republican govt in the us? was there a master mind behind all that?

Author

Scott,

I’d say so. After all, new boatloads of foreign mercenaries were being shipped to the North and paid well by Lincoln to fight against actual Americans, while these suckers who had been the Yankeeland for nearly 20 years were just gonna be cannon-fodder conscripts. Those who hate republicanism (most politicians, the managerial state, bankers, centralizers, industrial-capitalists, the corporate media) love permanent revolution. Who do you think was THE mastermind?

https://www.dissidentmama.net/puritans-part-5-redeeming-the-time/