By Daniel B. Rundquist

When I read the news lately, I just want to shout. It’s insane. There is no civility, no normalcy, and really not much in the way of actual news any longer. Even media outlets dedicated to reporting just the weather are polluting the airways with their political agenda. Propagandists of every political strip largely rule the airways today and this is both the symptom and cause of the divided nation we live in.

I would never suggest that free speech be quelled in spite of these issues. In fact, I would hope for the opposite; that we see new news organizations spring up that by virtue of their work on actual reporting of the news they rise to popularity in the marketplace of “news media.”

For now, however, we are left to seeking first-hand accounts of events instead of relying on any reporting of the event. For example, if one wishes to know what news came out of a presidential press conference, we need to watch the press conference ourselves because reporting of that press conference will be politicized by every single group reporting on it. The present media has lost all credibility at this point and the American people realize this.

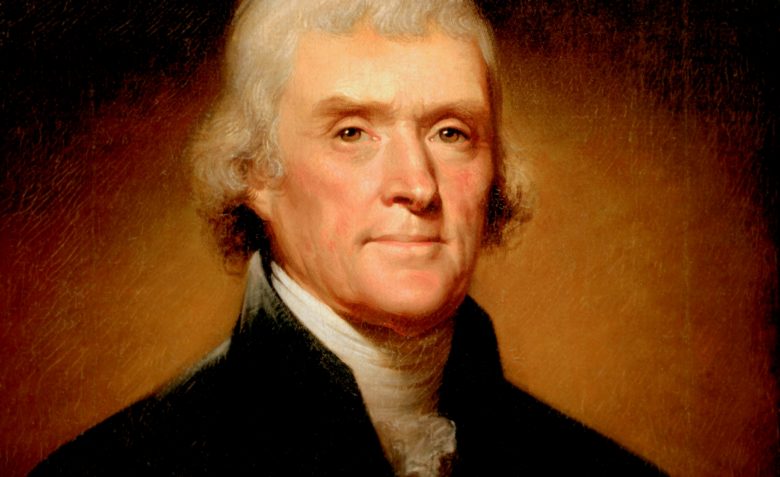

Corrupted media and contested elections aside, we are left facing the problems presented by living in what is now a hopelessly divided nation. While many groups are even now attempting to erase our Founders and Framers from the national identity of America by unlawfully tearing down statues and defacing memorials, we can still discover what a civilized America should be focused upon through the timeless words given to us by President Thomas Jefferson.

On March 4, 1801, President Thomas Jefferson delivered his first inaugural address to the people. The words of our poignant statesman are equaled by none since. What might we learn from him today?

“Friends & Fellow Citizens, Called upon to undertake the duties of the first Executive office of our country, I … express my grateful thanks for the favor with which they have been pleased to look towards me, to declare a sincere consciousness that the task is above my talents, and that I approach it with those anxious and awful presentiments which the greatness of the charge, and the weakness of my powers so justly inspire. A rising nation, spread over a wide and fruitful land, traversing all the seas with the rich productions of their industry, engaged in commerce with nations who feel power and forget right, advancing rapidly to destinies beyond the reach of mortal eye; when I contemplate these transcendent objects, and see the honour, the happiness, and the hopes of this beloved country committed to the issue and the auspices of this day, I shrink from the contemplation & humble myself before the magnitude of the undertaking.”

Here Jefferson not only expressed his gratitude of the electorate that supported his presidential campaign, but clearly understands the gravity of his duties in the office of the presidency. He approaches the office not as today’s politicians do, filled with a peacock’s pride and political braggadocio – but instead with a sincere sense of humility knowing that while he will use all of his abilities to do his best work, the role may require more than that.

“Utterly indeed should I despair, did not the presence of many, whom I here see, remind me, that, in the other high authorities provided by our constitution, I shall find resources of wisdom, of virtue, and of zeal, on which to rely under all difficulties. To you, then, gentlemen, who are charged with the sovereign functions of legislation, and to those associated with you, I look with encouragement for that guidance and support which may enable us to steer with safety the vessel in which we are all embarked, amidst the conflicting elements of a troubled world.”

Here Jefferson looks not to his own authority as president and executive to accomplish the task before him, but rather looks directly to the Constitution and the offices and processes that it provides. He looks to the legislative branch. Today, in sharp contrast, our political class looks only to themselves and their own power and control. No one even thinks of the Constitution in the manner Jefferson once did any longer, in fact for most politicians the restrictions of government overreach presented in the Constitution are dodged by crafty legislation and endless Executive Orders. The Constitution is something these politicians only hope not to get caught by with a legal challenge in court long after the fact.

“During the contest of opinion through which we have past, the animation of discussions and of exertions has sometimes worn an aspect which might impose on strangers unused to think freely, and to speak and to write what they think; but this being now decided by the voice of the nation, announced according to the rules of the constitution all will of course arrange themselves under the will of the law, and unite in common efforts for the common good. All too will bear in mind this sacred principle, that though the will of the majority is in all cases to prevail, that will, to be rightful, must be reasonable; that the minority possess their equal rights, which equal laws must protect, and to violate would be oppression. Let us then, fellow citizens, unite with one heart and one mind, let us restore to social intercourse that harmony and affection without which liberty, and even life itself, are but dreary things.”

Here Jefferson addresses the election outcome directly. The concept of free speech was relatively new in the world where every man was free to speak out without the threat of imprisonment or punishment as was the case in the rest of the civilized world at the time. This free speech of course led to the same heated discussions then as it does today. Jefferson’s wish is that all Americans, regardless of their opinions, will respect the rule of law as a source of unity. He asks for unity “… with one heart and one mind.” He does not demand that the losing party of the election abandon their ideas and conform to his views. The American President is not a dictator. This is a key distinction that must be remembered.

“Let us then, with courage and confidence, pursue our own federal and republican principles; our attachment to union and representative government. Kindly separated by nature and a wide ocean from the exterminating havoc of one quarter of the globe; too high minded to endure the degradations of the others, possessing a chosen country … entertaining a due sense of our equal right to the use of our own faculties, to the acquisitions of our own industry, to honor and confidence from our fellow citizens, resulting not from birth, but from our actions and their sense of them, enlightened by a benign religion, professed indeed and practised in various forms, yet all of them inculcating honesty, truth, temperance, gratitude and the love of man, acknowledging and adoring an overruling providence, which by all its dispensations proves that it delights in the happiness of man here, and his greater happiness hereafter; with all these blessings, what more is necessary to make us a happy and a prosperous people?“

“Still one thing more, fellow citizens, a wise and frugal government, which shall restrain men from injuring one another, shall leave them otherwise free to regulate their own pursuits of industry and improvement, and shall not take from the mouth of labor the bread it has earned. This is the sum of good government; and this is necessary to close the circle of our felicities.”

Here Jefferson presents his vision of how America generally proceeds; with principled confidence, with the enlightenment of faith and its tenants, with a government focused not on expanding itself but restraining its taxing and spending. This entire paragraph by Jefferson is completely ignored by our political class today as every new policy they foist upon the people is completely opposite of every sentence. Jefferson, however, provides for us an even more descriptive view of the expectations of government under his leadership:

“… it is proper you should understand what I deem the essential principles of our government, and consequently those which ought to shape its administration. I will compress them within the narrowest compass they will bear, stating the general principle, but not all its limitations.—Equal and exact justice to all men, of whatever state or persuasion, religious or political:—peace, commerce, and honest friendship with all nations, entangling alliances with none:—the support of the state governments in all their rights, as the most competent administrations for our domestic concerns, and the surest bulwarks against anti-republican tendencies:—the preservation of the General government in its whole constitutional vigor, as the sheet anchor of our peace at home, and safety abroad: a jealous care of the right of election by the people, a mild and safe corrective of abuses which are lopped by the sword of revolution where peaceable remedies are unprovided:—absolute acquiescence in the decisions of the majority, the vital principle of republics, from which is no appeal but to force, the vital principle and immediate parent of the despotism:—a well disciplined militia, our best reliance in peace, and for the first moments of war, till regulars may relieve them:—the supremacy of the civil over the military authority:—economy in the public expence, that labor may be lightly burthened:—the honest payment of our debts and sacred preservation of the public faith:—encouragement of agriculture, and of commerce as its handmaid:—the diffusion of information, and arraignment of all abuses at the bar of the public reason:—freedom of religion; freedom of the press; and freedom of person, under the protection of the Habeas Corpus:—and trial by juries impartially selected. These principles form the bright constellation, which has gone before us and guided our steps through an age of revolution and reformation. The wisdom of our sages, and blood of our heroes have been devoted to their attainment:—they should be the creed of our political faith; the text of civic instruction, the touchstone by which to try the services of those we trust …”

These, then, are the specifics of good government. They are standards which have almost entirely fallen by the wayside and clearly do not exist in today’s America. One could read each principle and ask, ‘are we doing this?” and the answer would be “no” in every case. We are no longer living in the America of or founding; we exist in a bizarre and twisted America reformed by the political class and shaped by a dishonest media. Jefferson foresaw that problems might occur in the adherence to these principles and even provided some direction for us:

“… and should we wander from them in moments of error or of alarm, let us hasten to retrace our steps, and to regain the road which alone leads to peace, liberty and safety.”

Jefferson concludes his message with the same introspective humility that he began his address with.

“I repair then, fellow citizens, to the post you have assigned me … I have learnt to expect that it will rarely fall to the lot of imperfect man to retire from this station with the reputation, and the favor, which bring him into it … I ask so much confidence only as may give firmness and effect to the legal administration of your affairs. I shall often go wrong through defect of judgment.“

“When right, I shall often be thought wrong by those whose positions will not command a view of the whole ground. I ask your indulgence for my own errors, which will never be intentional; and your support against the errors of others, who may condemn what they would not if seen in all its parts … Relying then on the patronage of your good will, I advance with obedience to the work, ready to retire from it whenever you become sensible how much better choices it is in your power to make.”

It is unlikely that any modern politician could meet or improve upon Jefferson’s approach to the American presidency. Our American culture has so devolved that his words are scarcely read and even less comprehended by a population distracted by so many other “shiny objects” today. Indeed, to the rest of the world, we appear to be little more than a nation of squirrels pausing in the center of the lane, trying to decide whether to cross the road or not.

Portions of Jefferson's address taken from that which was printed in the National Intelligencer, 4 Mch. 1801; “President’s Speech this day At 12 o’clock, THOMAS JEFFERSON, President of the United States, Took the oath of office required by the Constitution, in the Senate Chamber, in the presence of the Senate, the members of the House of Representatives, the public officers, and a large concourse of citizens. Previously to which he delivered the following Address."

If you haven’t checked out my interview with Daniel B. Rundquist from this fall, please do so. It’s a riveting discussion, if I do say so myself.