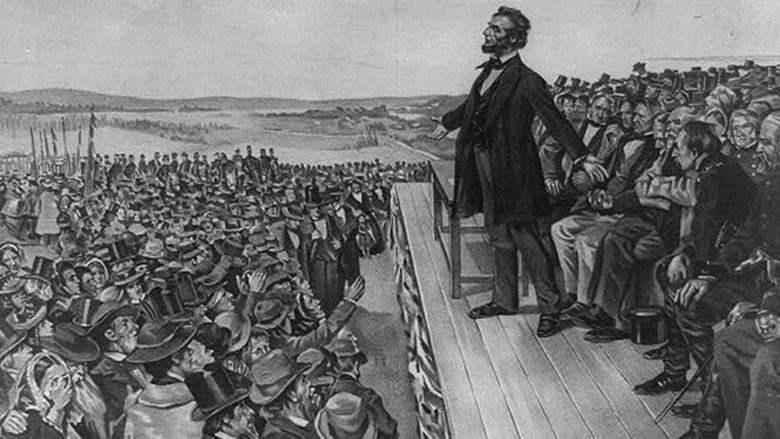

ON NOVEMBER 19, 1863, ABRAHAM LINCOLN delivered his most revered oration at the dedication of the Soldiers National Cemetery at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. As a work of English prose, The Gettysburg Address has few equals in the American literary canon. Eloquent and succinct, it has inspired Americans with almost religious awe for generations. It is one of the few instances of American oratory that has achieved a status akin to holy writ. It has become a kind of Nicene Creed that defines American orthodoxy. It is what “real Americans” believe about their historical origins, their foundational ideals, and their collective mission.

As the sesquicentennial of the Gettysburg Address came and went—some no score and almost seven years ago, that is, in 2013—a throng of articles, editorials, and commentaries poured forth from news outlets in praise of Lincoln’s oration that reminded us of the significant influence that these words have played and continue to play on the American psyche.

On the big day, the 13th of November in the year of our Lord 2,013, thousands gathered at the Soldier’s National Cemetery at Gettysburg, to remember, to commemorate, and to celebrate Abraham Lincoln’s most celebrated oration, The Gettysburg Address. Lincoln’s address was hailed not only for its eloquence, but for “inspirational” qualities, qualities which invigorated “national ideals” and provided Americans (including you and I, I reckon) a definition of “what a nation should be.” (Why, thank you, Mr. Lincoln!)

Keynote speaker James McPherson, the (in)famous Civil War historian and presiding high priest of the event, praised Lincoln’s oratorical achievement in which he claimed, among other things, “weaved together themes of past, present, and future; continent, nation, and battlefield; and birth, death and rebirth.”

The event was preceded by a quasi-religious orgy of praise and adulation in the media. Articles and editorials from news outlets from across the fruited plains joined in the chorus in praise of Lincoln’s address. One newspaper in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, even apologised over an editorial written by a staff member in 1863 who was critical of Lincoln’s address. This despite the fact that the reporter was actually there.

Apparently the staff of the 21st century of-this no- account newspaper thought themselves a better judge of Lincoln’s creation myth—mystically summoned from I-know-not-where—than the reporter on the scene who—like any other person of his time that knew even a scintilla of history as it related to America’s origins and form of government— was not duped by the pretty, albeit, scandalous words.

Their reason for this 150-year-old retraction?

Well, the man who actually attended the event and heard the address from Lincoln’s own lips was—as you may have already guessed —on the “wrong side of history”! (I could spend hours on what is wrong with the notion of history having sides, but one hopes that such a statement self-evidently crazy and a product of a “special” way of thinking.)

(If you think this kind of hindsight apology on the part of a newspaper is unique, the UK paper The Guardian apologised a couple of weeks ago—07 May 2021, to be exact—for supporting the Confederacy during the War and saying bad things about Mr. Lincoln. I guess they know better than those who lived at that time too! Seems rather arrogant, not to mention audacious, to me.)

Not to be outdone in the sesquicentennial celebration, the Public Broadcast System (PBS) trotted out their fundraising ace in the hole, Ken Burns of PBS’s “The Civil War” fame, for a new “documentary” called “The Address.” PBS described the production is described as

…a 90-minute feature length documentary … [that] tells the story of a tiny [government indoctrination camp—Just kidding—sort of …] school in Putney, Vermont, the Greenwood School, where each year the students are encouraged to practice, memorise, and recite the Gettysburg Address. In its exploration of the Greenwood School, the film also unlocks the history, context and importance of President Lincoln’s most powerful address.

To build momentum for the new documentary and get folks involved, people all over the country—all over the “nation,” in their words—were encouraged to memorise the Gettysburg Address and upload a video of them reciting it. I counted 1342 uploaded videos on the LearntheAddress.com web site.

You might recognise the names of a few of the participants:

Presidents Jimmy “P-Nut” Carter, King Bush the First, Little Bush (AKA “Shrub”), and Barry Obama(lama-ding-dong). Other participants included the always charming and lovely Nancy Pelosi of the US House of non-Representatives; the always insightful and impartial Wolf Blitser of CNN, financial hot dog Warren Buffet; the heretofore missing in action queen of 70s comedy Carol Burnett, philanthropist nerd Bill “The Vaxinator” Gates, Whoopi “WTF” Goldberg of the always entertaining and informative daytime drama, The View, Jimmy “I always look stoned” Kimmel of Late Night fame, Newswoman (we think) and political commentator Rachel Maddow, America’s favourite Irish-Americans, Conan O’Brien and Bill O’Reilly and the New England financial guru and home décor diva Martha Stewart.

With this cast of characters endorsing the project—many, many illustrious names having been omitted to save space—you might ask:

“Who are you, Graham, to analyse or criticise Lincoln’s ‘inspirational’ address when so many luminaries, including experts, politicians, reporters, newscasters, performing artists, and giants of industry and finance clearly reverence the address and believe in the veracity of its contents?”

Well, friends, I will freely admit it—I’m nobody much compared to those hot shots; but I do like consistency.

To be honest, nothing would please me better to be wrong about where I’m about to take you, but I sincerely believe that truth is good and desirable for its own sake—even if it flips the American Creation Myth on its head and makes the stable of intellectual heavyweights enumerated above look a little less wise (to put it politely) …

I will be the first to admit that the words of the Gettysburg Address are pretty, indeed, lofty, stirring, enchanting—even mesmerising—but such considerations only address questions of FORM and not SUBSTANCE.

The question that was never raised—at least in anything I read or saw—during the anniversary of Lincoln’s speech and its aftermath was whether or not the pretty words were TRUE.

Now that I’ve burdened you with way too much in the way of prefatory remarks, let’s get into the meat and potatoes, so to speak, of the topic at hand by taking a line-by-line look at the text of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address:

(Ok. Deep breath. Here we go!)

“Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation …”

As much as Lincoln may have wished it to be the case, no new nation was brought forth on the American continent “four score and seven years” before his speech.

In 1776, thirteen English colonies, with thirteen different governing bodies (out of 20 English colonies on the continent and many others in the Caribbean), collectively declared the reasons why they thought it necessary to secede from their mother country. They were “held together” by common practical interest, nothing more. It was mutually beneficial to unite for the purposes of defence against an aggressor that meant to subjugate and deny them the “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” to which they had come to enjoy over the course of many, many years. The colonists were not inventing something new; they were protecting something old, namely, self-government and their inherited rights as Englishmen.

There was no formal agreement binding those particular colonies together in 1776.

The Articles of Confederation would not be ratified by all of the colonies (now independent States), until 1781. But since that document expressly declared that each State retained (not gained) its “sovereignty, freedom, and independence,” one would be hard-pressed to call this union of States a “nation,” in either the ancient or modern sense of the word.

The United States Constitution—which terminated the compact created by the Articles—would not go into effect until the summer of 1788, when 11 of the 13 States ratified it, although only 9 States were required to make the document binding on those States so ratifying. (They didn’t pull the proverbial trigger until they got New York and Virginia signed-up, so they waited on them; hence, 11 before it was formally established.)

If this created a nation—one and indivisible, as they say—then the States that ratified it were ignorant of this crucial detail and would not have adopted it if they thought that it did.

What was the status of States, one wonders, that had not yet ratified the document at the time it was formally adopted?

Of course, they either remained under the Articles, or they carried on “unattached” until they were. They were most certainly not part of nation created in 1776 and from which there was no escape—never ever—regardless of the reason.

Who would sign up for such a horror without a gun in their mouth or bayonet in their breast? Seriously. Who would?

“Let us free ourselves from the British Empire, guys, and make an indivisible nation! Yea!”

Sure, man. Totally believable.

Given the foregoing, this leads us to the obvious and irrefutable conclusion that since there was no nation in 1776, 1781 or 1788, there was no “nation” when Lincoln’s speech was delivered in 1863 (or today, for that matter).

There had been a voluntary union of States created by the US Constitution, but by 1861 this political arrangement—like the union created by the Articles of Confederation—had been terminated by the solemn conventions of eleven sovereign States.

The only thing that had occurred “four score and seven years” before Lincoln’s address was that thirteen independent political societies seceded from a government that they viewed as hostile to their way of life. Nothing more.

“Conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal…”

This reference to “the equality of men” in the Declaration of Independence of 1776, takes a five-word phrase out of a document of over 1300 words and imbues it with meaning which cannot be derived from either the document itself or the historical context in which it was written.

The notion of equality expressed by Mr. Jefferson has nothing to do with the modern doctrine of egalitarianism (i.e., the belief in the absolute political, social, and/or economic equality of all persons as an end to be realised), but is rooted in social contract theory, a popular political theory of the time; primarily, but not exclusively inspired by (if not copied from) the works of John Locke. Although an overview of this theory and how it is utilised in the Declaration is outside the scope of this article (although I will be addressing it in elsewhere in this book), we are certainly justified in saying that the specificity with which Jefferson justifies the separation of the American colonies from the King’s rule does not lend itself to interpret the proposition “all men are created equal” as a general or universal self-evident truth (whatever that might mean), but rather one situated in a specific set of circumstances and between specific parties.

Lincoln, of course, was not trying to convey anything that had to do with the actual meaning or intent of the author of the Declaration of Independence. Lincoln evokes the language of the Declaration of Independence to give his imaginary nation an air of legitimacy.

Since there was no nation conceived in the manner put forth by Lincoln—the proposition to which it was said to be dedicated is a moot point.

__________________

Author Aside

Even though the proposition to which the so-called nations is, in fact, a moot point, the meaning of the word “proposition” ought to be defined so as to better understand the claim being made by Lincoln. This being the case, I would like to say a few words about the word “proposition” and how been employed traditionally philosophers and logicians over the ages. A proposition, simply put, is a statement with a truth value, i.e., a statement that is either true or false.

“What time is it?” is not a proposition. It is a question, and as such, does not have a truth value—it cannot said to be true and it cannot be said to be false.

“It is 3:33pm,” on the other hand, Is a proposition. It does have a truth value. It is either 3:33pm or it is not 3:33pm. We have to check our watch, clock, or mobile device to determine it truth or falsity. Exclaimations are another example of non-propositional language. “Wow!” is neither true or false. With me so far?

There are, however, different kinds or classes of propositions, but they can all be placed in one of these three categories:

• TAUTOLOGIES, or statements that, by their very construction, are always true. For example, “Either it is raining outside, or it is not raining outside.” We don’t need to look out the window to know that this proposition is true

• CONTRADICTIONS, or statement that, by their very construction, always false. For example, “It is raining outside and it is not raining outside.” Once again, we do not need to look out the window to determine that such a proposition is false

• DESCRIPTIVE, or statements that can be either true, or false, but not both. For example, “It is raining outside.” One does have to look outside to determine whether this proposition is true or false.

Of these three kinds of propositions, only the first two, tautologies and contradictions, are self-evidently true or self-evidently false, that is, undeniably true or false without reference to anything outside of the structure of the proposition. The third , descriptive propositions, are not self-evident. It requires something more, usually observation, to determine whether it is true or false.

It is Lincoln, not Jefferson, that employs the term “proposition” and as a lawyer—a successful one at that—he knew what this meant.

This being the case, should be obvious that the proposition “All men are created equal” is not a tautology, neither is it a contradiction and, therefore, is a descriptive statement, a statement that requires us to look outside of what it says in order to determination whether or not it is true or false.

Setting aside the notion of “created” in the proposition “all men are CREATED equal” for the time being, how might we determine if men are in fact equal—the descriptive character not being obvious from the proposition itself.

When I look out into the world, I see people who look different, have different levels of intelligence, some are better at some things than others… We have people who are healthy and people who are sick, rich people, poor people, and people somewhere between the two; I see people with different beliefs, values, wants, desires, needs, etc.

I, for example, am not very good at sports. A lot of my friends are. They are better at sports than I am. This being the case, at least with regards to our sporting abilities, we are not equal.

I think it is safe to say that we are not born equal—either in ability or circumstance—but maybe it is the “created” bit that should be our focus, even though, admittedly, it is not something that can be pursued scientifically or even by casual everyday observation.

This puts the proposition that “all men are created equal” into a religious or mystical understanding of this descriptive statement, which could easily open thousands of interpretations—perhaps self-evident according to a kind of faith, but in such a case, it would be self-evidently understood in different ways by different people under shifting sets of circumstances. In fact, an understanding in this light, could justify all kind of claims which may or may not have merit or improve the state of mankind—it would depend on who was evoking the mystical proposition and what they hoped to accomplish with it.

This is important only insofar people believe these united States are a NATION dedicated to a PROPOSITION. People don’t dedicate themselves to propositions, generally speaking, but ideologies often do. If a government, believing itself to rule a nation dedicated to a proposition, we can expect that they will use their authority and means to make men equal, as they happen to define it, and we will be the Guinee pigs in their various experiments trying to bring about this unnatural state of affairs. By this I mean only that decisions will be made not on how people actually ARE, but how they believe they OUGHT to be. Ought is tricky and belongs to the field of ethics or moral philosophy. Ought requires a metaphysical foundation. Ought takes us away from a proposition demonstrably true or false, and lead us down a path of chaos, confusion, and everything that goes with it. Ought has to be enforced if it is to be realised. This should make just about anyone who has interacted with the government at any level a little uneasy.

It is for this reason that it is my opinion that even if we were a nation (which we are not) dedicated to a proposition (which we are not), it is a bad idea for a nation, any nation, to dedicate themselves to a proposition, any proposition. Nothing good has ever come from such a thing and nothing ever will if history or human experience born out over time and sifted out over multiple generations, is any kind of guide. When someone or a collection of someones with money, power, and a standing army think that people over which they claim to rule ought to be a certain way and not another regardless of their consent or will, look out!

__________________

“Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure…”

Words matter. Ideas have consequences.

A “civil war,” by definition, is a war between two or more parties, each of whom are fighting to control a single government. Everyone knows this, yet the nationalist—heirs of Lincoln—refuse to concede this very basic and incontrovertible linguistic point.

The conflict over which Mr. Lincoln presided was not a war over who would govern the political cesspool on the banks of the Potomac River (Washington, DC), but rather—and this is the long and short of it—it was a war for independence (that is, government by the consent of the governed) on one side and a war of invasion, conquest, and subjugation on the other.

(This fact, in my opinion, is the “Rosetta Stone”—the key—that unlocks all subsequent interpretations of American History—including the one invented by Lincoln.)

Because there was never a nation conceived in the way described by Lincoln, or dedicated to any abstract proposition such as equality, there was no legal or moral justification for Lincoln’s invasion of the Southern States. (Period. Full Stop.)

If the political entity created by the U.S. Constitution actually made a nation, then it could not logically be broken-up. A nation, by definition is one thing. However, the Constitution did not create a nation; it created a union. A union, by contrast is not one thing, but a plurality—two or more existing parties joined together by contract or agreement for specific purposes. By falsely describing the American union as a nation, Mr. Lincoln could call the conflict a civil war without credulity and rhetorically justify holding it together by force. This reasoning, however brilliant, was patently false then and is patently false today.

“… We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live… The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced… [and] gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain …“

After recounting the mythological birth of Lincoln’s nation, we must take courage as we look at the consequences of this false rendering of history. Its legacy is blood, rivers of blood—blood not shed to save a nation, but rather to create one by force of arms. Lincoln’s words are not only untrue, they also make a mockery of the dead that he “memorialised” in his address.

There was no nation to save and, therefore, there is no unfinished work for “us” to continue—at least not any work that existed prior to the war.

Insofar as the War created a nation—albeit one born in blood and not in law, tradition, or unfettered consent of the governed—it also created a mission. But let us not allow ourselves to obscure the obvious: this mission is innovation; it is revolutionary and ingrained in a false understanding of what actual people, at some actual time, actually said and actually did during the period under discussion.

It has nothing whatsoever to do with the cause of 1776 or the union that was created by either the Articles of Confederation or the U.S. Constitution.

Once a swindle of this magnitude is accomplished, the guilty party is obliged to cover up the crime or suffer the consequences. The Gettysburg Address is certainly among the most eloquent alibis in history.

As much as we may whence at the implication of such an assertion, we must not look the other way. The Union soldiers—note the absence of “national” in this appellation applied to the US military throughout the war—under Lincoln’s command were not holy warriors fighting for either a nation or a proposition, they were victims of ambition and revolution instigated by the head of a new sectional political party—the Republicans.

Those men’s blood, those men who lay in the dark, dank earth as Lincoln spun his tale, was only shed in vain if we refuse to call their slaughter what it was, seek to prevent any such thing from happening again under such false pretences, and bravely cast the blame where it belongs!

“That this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

These are, by far, the most audacious statements of the address!

A new birth of freedom for whom? A government of, by, and for what people?

He doesn’t say. It is such a sweeping and grand statement that just about anything could be read into it.

Well, almost anything. I don’t think that Self-government for the Southern people could be read into this speech. In fact, they would, in the name of self-government, be invaded, sacked, burned, pillaged, raped, and left in utter ruin because they had the temerity to assert the right to govern themselves as their fathers had done in 1776—without anyone’s permission, I might add.

* * *

American journalist, essayist, and magazine editor, H.L. Mencken (1880-1956) pointed out the absurdity of the doctrine expressed in the Gettysburg Address in a 1922 sketch on Lincoln. His words are as powerful now as they were then:

Think of the argument in it. Put it into the cold words of everyday. The doctrine is simply this: that the Union soldiers who died at Gettysburg sacrificed their lives to the cause of self-determination – that government of the people, by the people, for the people, should not perish from the earth. It is difficult to imagine anything more untrue. The Union soldiers in the battle actually fought against self-determination; it was the Confederates who fought for the right of their people to govern themselves.

Let’s repeat that last sentence again: “The Union soldiers in the battle actually fought against self-determination; it was the Confederates who fought for the right of their people to govern themselves.” Let that sink in for a moment …

Lincoln Historian and Pulitzer Prise winner Garry Wills called the Gettysburg Address “a giant, if benign, swindle.” (Emphasis added.) Lincoln’s words, although admittedly false, accomplished a great many things in Mr. Wills’s estimation. It (1) created a “different America” by (2) clearing “the infected atmosphere of American history” and (3) cleansing the Constitution. Best of all, for Mr. Wills, Lincoln’s words gave the American people (some of them, at least) (4) “a new past to live with that would change their future indefinitely …”

A new past! Goodness gracious!

The Gettysburg Address was certainly a “giant swindle,” as Wills observed, but it was most assuredly not “benign.” It was and is a malignant and cancerous lie—a lie that cost untold numbers of lives, an unaccountable loss of blood and treasure, and worst of all, continues to spread a diseased understanding of America right down to our own day.

Generations of Americans have already and will continue to stumble under the weight of this falsehood. Coupled with the violence that enforced this view of history, it forever destroyed the America of the founding generation. While some believe this to be a fortunate outcome, it came at the expense of the ability of normal, rational thinking Americans to reasonably access where they are, how they got there, and—to paraphrase the immortal words of Rodney King—why we can’t “just get along.”

Admittedly, words can do a lot of things, but despite their many powers, words cannot transform a fib into a fact. They cannot change the past; cannot change the terms of a compact; and they most certainly cannot create a nation out of thin air!

Neither the court historians, nor the media, or even the might of the United States government can make the words of the Gettysburg Address correspond to reality. They can only perpetuate the lie; guard the lie; and ridicule those who attempt to expose the lie—if they are lucky!

The lie—at least until recently—seemed secure. Social Justice, Critical Race Theory, and a growing throng of strange post-modern ideologies are trying to replace this nationalist myth with another nationalist myth, equally flawed as it relates to what America is, including, of course, the proposition to which it is supposedly dedicated.

The 1619 Project, no less than former President Trump’s 1776 Report, both suffer from the same derangement—belief in the “Proposition Nation.”

Both are rooted in a falsification of the plain facts of history readily available to anyone with an internet connection or library card (if they have inner-library loan) and a little ambition.

Unlike other creation myths dismissed out of hand for not having enough evidence, the position I have attempted to articulated has the following items to clearly illustrate the nature of the Union created by the founders under the compact styled the “Constitution for the United States of America.”

(Note that it is not called the “Constitution for the United People of America,” or “Constitution for the United Administrative Political Subdivisions of America,” but the “Constitution for the United STATES of America.”)

In brief, this is what we got:

1. Notes on the Constitutional Conventions by actual participants (Which, of course, show how the framers of the Constitution understood the meaning of the document and the nature of the Union it proposed to establish)

2. The proceedings of the States’ ratification conventions (Which show how each of the ratifying States understood the nature of the proposed Union and the terms and conditions created by its adoption)

3. The Constitution itself (Which, you might at this point guess, says nothing about the creation of a national or centralised government, neither does it establish a national mission statement, including the proposition to which the non-nation is purportedly dedicated)

4. The writing of the proponents of the proposed Constitution, the Federalist (why they thought adoption was a good thing and how they argued it)

5. The writing of the opponents of the proposed Constitution, the Anti-Federalist (why they thought adoption was a bad thing and how they argued it)

6. Correspondences and other writings of the participants involved in both the creation and adoption of the Constitution

7. The newspapers and other publications of the time period in question

8. The arguments on the nature of the Union, for example, the famous Webster-Haynes debates and other debates recorded or written prior to the War to Prevent Southern Independence and/or

9. Other non-primary sources that straighten things right out by employing the kinds of documents I have just enumerated. I will mention two, although there are other worthy candidates for your consideration:

• Able Upshur’s A Brief Enquiry Into the True Nature And Character Of Our Federal Government

• Albert Taylor Bledsoe’s Is Davis a Traitor: Or Was Secession a Constitutional Right Previous to the War

This is a lot of documentary evidence by any standard!

Given the forgoing, I can only conclude is that the Gettysburg Address is “nonsense on stilts” and a dangerous lie that has the power, clearly has the power, to alter one perception of reality—past, present, future—and not in a good way!

There are a few other points I hope you carry away with you after going through the position argued above—why I think it matters …

➊ Our understanding of where we are and how we got here cannot give us the bearings we need to chart a course for where we want to be if it is based on a falsehood. This applies to many things, including, but not limited to, the nationalist creation myth found in the Gettysburg Address.

➋ Words matter. Ideas have consequences. Sometimes bloody consequences.

➌ It is better to be right than to be wrong if it can be helped. The acquisition of knowledge breads confidence, poise, and the ability to clearly articulate your position without resorting to argument or the deployment of logical fallacies such as ad homimen attacks—one used ad nauseum by people who hate us.

AND FINALLY,

➍ if we wish to see that the true history of our Confederate fathers is preserved for future generation, we must get the history of our Confederate fathers’ fathers exactly right.

When we do, it is plain to see and exhilarating to know—even in these dark days of cultural revolution and an unnatural hatred towards our people and our symbols—that THE SOUTH WAS RIGHT!

When you get that bit right, everything else—especially history, politics, and never-ending noise and chaos coming from the media, especially as it relates to America, falls right into place!

I, for one, think this is a fine thing—an exceptionally fine thing indeed!

Philosopher, publisher, and writer Paul C. Graham graciously let me cross-publish this treatise. It has only been shared in part with the Wade Hampton SCV camp in Columbia, SC, and will most likely be included in whole in his forthcoming book “Southern Woke” comprised of his essays, speeches, observations, and aphorisms. To learn more about Graham, click here, and to download a free digital edition of his book “Confederaphobia,” click here.

Comments

What an honour! Thanks DM!

Author

I mean, you ARE my bruthah from another muthah, so there’s always that, lol! 😉

But seriously, I’m just happy you are writing such good stuff and are willing to let me cross-pub the goods. As you like to say, keep the skeer on!

When the Founders referred to “men being created equal” they did NOT mean “all men are identical” or “each human being is identical to every other human being”. Hardly! They were referring to the dominant social-structures of European societies and the institutions of hereditary social status,hereditary titles and offices,etc. – the things so salient in European,and British,societies. In other places,the Founders exclude hereditary titles and the acceptance from foreign princes and powers of European titles of class distinction and social status by US citizens. So,the US would not end up being littered with “princes,dukes,earls,margraves,knights,lords and ladies”.

Great point and Jefferson may have had that sort of thing in mind, but they use of titles was not listed, as I recall, being numbered among the reasons for secession. The use of the language of Social Contract theory, which is what the preamble had to do with a primitive equality, which I have come to believe is the key to understanding this Enlightenment nonsense, but an explanation of this requires more than a blog comment to cover…

Locke adapted Hobbes and Jefferson adapted Locke. What they all retained was the thought experiment Hobbes called “the state of nature.” The equality in this state (although imaginary) is what Jefferson used in the preamble—or , at least that is my working hypothesis. I believe it was a mistake, and others who were if a classical turn of mind never cared for it.

I’ll think about your comment as I work on the Declaration and Social Contract Theory.

Thank you for your comment. I know DM likes to see some interaction in the comments Section of her blogs!

PG

Author

Gentlemen,

Juicy, juicy stuff! Yes, I love these kinds of interactions and these types of thought processes makes me even more excited to read your forthcoming book, Paul.

And Joseph, thank you for reading Paul’s deep treatise and offering up such thought-provoking points and sharing them with us.

Here’s to free-thinking and rigorous debate, y’all – that’s the good stuff for sure!